Subscribe to the podcast: iTunes | Stitcher | RSS

The Rose Hill Church congregation, 1967

Bill Ferris grew up on a farm in Warren County, Mississippi, along the Black River. His family, the only white family on the farm, worked side by side with the African Americans in the fields. When he was five, a woman named Mary Gordon would take him every first Sunday to the small black church on the farm: Rosehill Church.

When the congregation was singing, you could hear those hymns for a mile or more. They would waft across the countryside. There’s nothing more beautiful in that quiet, still morning with the sound of the hymns coming into your ear.

When Bill was a teenager he got a reel-to-reel tape recorder and started recording the hymns and services.

I realized that the beautiful hymns were sung from memory — there were no hymnals in the church–and that when those families were no longer there, the hymns would simply disappear.

These recordings led Bill to a lifetime of listening to and documenting the world around him — preachers, workers, storytellers, men in prison, quilt makers, the blues musicians living near his home (including the soon-to-be well known Mississippi Fred McDowell): “For me that was a clear mission in my life, and it grew out of that world of the farm.”

Bill became a prolific author, folklorist, filmmaker, professor, and chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities. He is a professor of history at UNC–Chapel Hill and an adjunct professor in the Curriculum in Folklore. He served as the founding director of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi, where he was a faculty member for 18 years. He is associate director of the Center for the Study of the American South.

His thousands of photographs, films, audio interviews, and recordings of musicians are now online in the William R. Ferris Collection, part of the Southern Folklife Collection at the University of North Carolina.

In June 2018, the Dust to Digital label released a 3-CD box set of his recordings, Voices of Mississippi: Artists and Musicians Documented by Bill Ferris — nominated for a Grammy Award. But the inspiration for his many accomplishments remains the people in his rural farm community.

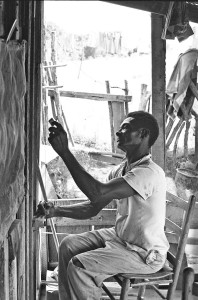

Ferris and his brother worked alongside the African-American families who lived on their farm

Louis Dotson

Louis Dotson made a one-strand guitar with wire unwound from a broom handle then attached to the front wall of his house. He plucked the string with a metal object while sliding a small bottle to change its pitch. Dotson also “blew the bottle” — a small Dr. Tichenor’s Antiseptic bottle or larger Coca-Cola bottle — changing his pitch by adding water.

Ever since I was a little bit of a boy, I used to blow the bottle. Me and another boy, name of Richard Coleman, used to blow them Coca-Cola bottles. He was a little older than I was. We was raised up together. We’d be down there at Brassfield’s Store all the time.

Richard used to live on one hill, and I lived on another one. We’d blow them bottles to call one another. See, when I’d blow in the bottle and whoop in it, he’d know what I meant. If he’d blow in his and whoop in it, I’d hear him, and I’d go to him. We’d meet up then, see. We’d always carry a bottle around with us so we’d be able to get to one another. We called that “talking the bottle.”

See, you have to fill that Coke bottle a little over half full of water. You can blow and whoop in it then. If you don’t have the water in it, it takes up too much air, and you can’t do no whooping.

–Louis Dotson

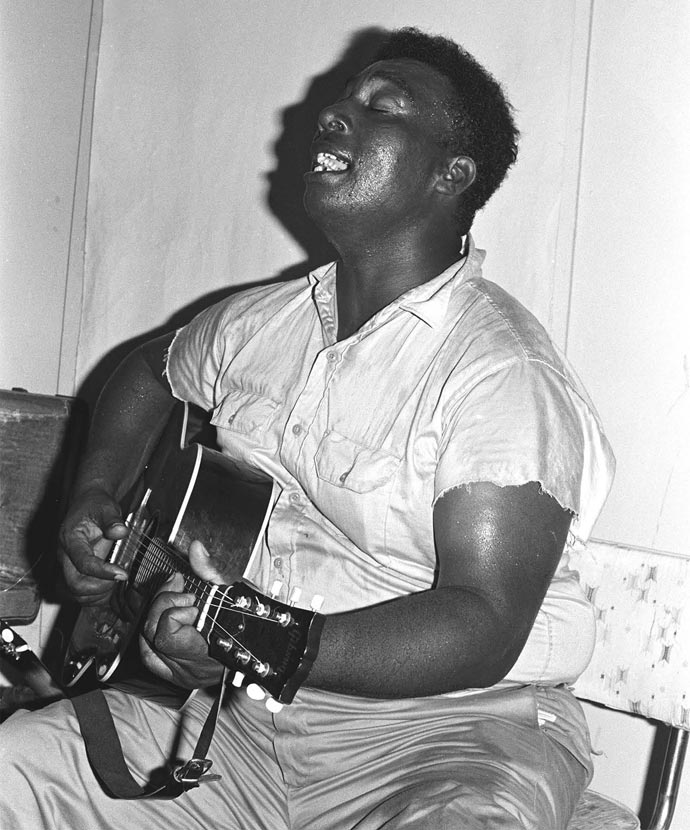

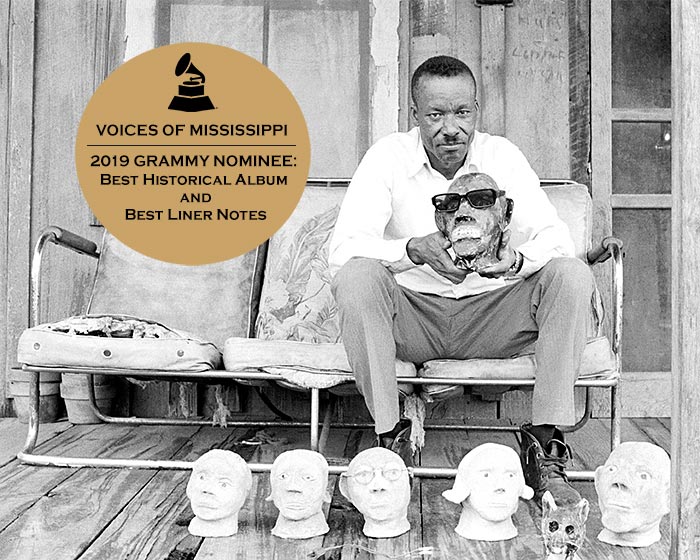

James “Son Ford” Thomas

In 1968 Bill met James “Son Ford” Thomas, a storyteller, sculptor, and Delta blues singer/guitarist from Leland, Mississippi. They remained close until Thomas died in 1993.

My granddaddy used to play that song “Little Red Shoes” for white people at dances. He played them old-time blues. He used to keep a gang around the house all the time. He’d play guitar and tell funny jokes, and it’d be just like we was selling whiskey, there’d be so many people there.

“The first guitar I owned was in 1942. I picked enough cotton to pay for that. I ordered me a guitar out of Sears and Roebuck, a Gene Autry guitar. It cost eight dollars and fifty cents. After I got my guitar, I wouldn’t pick no more cotton. That was it. That’s how I learned to play the guitar.

The blues has been out so long, you can’t hardly tell where it started. My granddaddy was about seventy-five years old when he died, and I used to hear him talk about the blues. There must have been blues before his time because there was blues when he was a boy.

I think there always was the blues. They come from the country. You take a long time ago, you’d catch fellows out in the field plowing a mule. You’d hear them way down in the field late in the evening singing the blues. That’s why I say blues come from the country.”

–James “Son Ford” Thomas

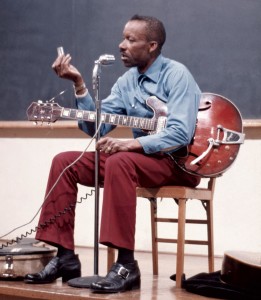

Sonny Boy Watson

Sonny Boy Watson at his home in Stoneville, Mississippi, 1968

Through his friend Son Thomas, Bill met other blues musicians: “I tried to record people and document the person. I would try to get to know someone like Son Thomas and then go deeper and deeper into their life. As you got to know him better, you discovered a circle of friendships around him.”

Bill spent much of 1968 recording a slew of great guitarists and singers, each with their own style. One standout was Sonny Boy Watson.

Scott Dunbar

Scott Dunbar led fishing and hunting trips, always with a guitar in tow. He recorded one album, released in 1972 titled From Lake Mary, named for his hometown. Here are its liner notes:

Scott Dunbar: born 1904, son of an ex-slave, on Deer Park between the Mississippi and Lake Mary (an eleven mile cut-off arm of the River) west of Woodville and south of Natchez, Mississippi. He made a guitar out of a “cigar box and a broomstick and some stream wire” when he was eight and played it like a violin.

When he was ten he got a real guitar and began teaching himself to play. “My father died,” he says, “and then my mother moved to Natchez, and she died. I came on this side of the Lake and I been livin’ on this side ever since. Old Lee Baker, he played fiddle, and he came over and said, “C’mere boy, I want to hear you play that guitar,” and he brought me over to this side to play with his band.

The congregation

The Providence Missionary Baptist Church

Bill documented gospel singers and sermons across the state. He and his tape recorder often attended the Rose Hill Church in Vicksburg, the Church of God in Christ in Clarksdalen and the Providence Missionary Baptist Church in Paulette.

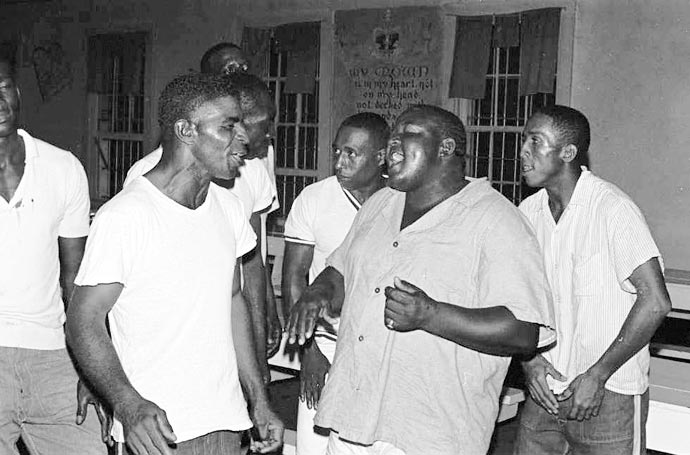

Parchman Farm prisoners

Walter Lee Hood performs gospel music with other inmates at Parchman Farm, 1968.

Another source of religious songs was Parchman Farm, the Mississippi State Penitentiary. The famed folklorist Alan Lomax recorded there in the late 1940s. Bill Ferris followed his footsteps 40 years later to audio-tape the gospel and blues music sung by the inmates. A particularly talented singer, Walter Lee Hood, often took the lead.

Alice Walker

Alice Walker at Yale University, 1976

Bill began teaching at historically black Jackson State College (now University) in 1970. Months before at a student protest police gunfire killed two people and injured twelve were during a student protest. It happened eleven days after Kent State, but barely made the national news.

“It was a very powerful time. People said they were ‘behind the stockade’ at Tougaloo [College] and Jackson State,” said Ferris. “Alice Walker and her husband Mel Leventhal were close friends, as was Ernst Borinsky who taught sociology at Tougaloo. It was an amazing experience to learn about a historically black college and its worlds.”

Bill spent many hours recording southern stories and storytellers, such as Walker, Alex Haley, Robert Penn Warren, Barry Hannah, and B.B. King.

Photos of Mississippi

The Southern Folklife Collection at the University of North Carolina houses the complete William R. Ferris Collection, 1910s-2016. It totals about 250,000 items (604.5 linear feet), with much of it digitized and now online. You can listen to his audio recordings, watch his films, and click through his photos.

Here’s a slideshow gallery of a few of the images there:

[metaslider id=7537]

Voices of Mississippi: Grammy-Nominated

The record label Dust to Digital put out three CDs in a box set titled William R. Ferris Collection, 1910s-2016: “This watershed release represents the life’s work of William Ferris, an audio recordist, filmmaker, folklorist, and teacher with an unwavering commitment to establish and to expand the study of the American South.” The collection received two Grammy Nominations for Best Historical Album and Best Liner Notes.

The wonderful booklet that comes in the package contains the audio and photos on this webpage. The cover (below) pictures James “Son Ford” Thomas sitting on his porch with a few of his sculptures.

Below is the album tracklist with a few more audio selections:

This story was produced by Barrett Golding with The Kitchen Sisters for The Keepers.

“Keepers is an important word. What do we keep? How will our memories be kept? One of the most tragic things for people is to be forgotten. Blind Lemon Jefferson sang, “One kind favor I ask of you. See that my grave is kept swept clean.” The keepers of our culture, are sweeping those graves, never forgetting the worlds that form our lives as individuals, as communities, as a nation, and as a globe.” –Bill Ferris