[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/1″][vc_column_text]

RECIPES | SCHOLARS | MUSIC | EXTRAS | LINKS

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][metaslider id=2071]

Story #4: Hidden Kitchens Russia—Dissident Kitchens

When Nikita Khrushchev emerged as the leader of the Soviet Union after Stalin’s death in 1953, one of the first things he addressed was the housing shortage and the need for more food. Thousands of people were living in cramped communal apartments, sharing one kitchen and one bathroom with sometimes up to 20 other families.

“All the people wanted to live in their own apartment,” says Sergei Khrushchev, the son of Nikita Khrushchev. “But in Stalin’s time you cannot find this. When my father came to power he proclaimed that there will be mass construction of apartment buildings and in each apartment will live only one family.”

They were called Khrushchevkas, Khrushchev apartments. Five story buildings made of prefabricated concrete panels. “They were horribly built, you could hear your neighbor,” says Edward Shendrovich, venture investor and Russian poet. The apartments had small toilets, very low ceilings, and very small kitchens. “No matter how tiny it was it was yours,” says journalist Masha Karp from Leningrad, who worked for the Russian Service of the BBC. “This kitchen was the place where people could finally get together and talk at home without fearing the neighbors in the communal flat.” Khrushchev introduced a completely new era in Soviet life. “It was called a thaw and for a reason,” says Masha Karp. “Like in the winter when you have a lot of snow but spots are already green and the new grass was coming,” says dissident writer Vladimir Voinovich. “In Khrushchev times it was a very good time for inspiration. A little more liberal than before.“

Kitchen Table Talk

The individual kitchens in these tiny apartments became hot spots of culture. Music was played, poetry recited, underground tapes were exchanged, forbidden art and literature circulated, politics debated, and deep friendships were forged in the the kitchen. “One of the reasons why kitchen culture developed in Russia is because there were no places to meet,” says Edward Shendrovich. “You couldn’t have political discussions in public, at your workplace. You couldn’t go to cafes – they were state owned. The kitchen became the place where Russian culture kept living untouched by the regime. It was the beginning of dissident kitchens.”

These “dissident kitchens” took the place of uncensored lecture halls, unofficial art exhibitions, clubs, bars, dating services. “The Kitchen was for intimate circle of your close friends, says Alexander Genis, Russian writer and radio journalist. “When you came to the kitchen, you put on the table some vodka. And something from your balcony, not refrigerator, but balcony, like pickled mushrooms. Something pickled. Sour is the taste of Russia.” Furious discussions took place over pickled cabbage, boiled potatoes, sardines, sprats, herring.

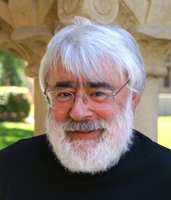

“Kitchens became debating societies. remembers Gregory (Grisha) Freidin, Professor of Russian Literature at Stanford University. “Even to this day political wind-baggery is referred to as kitchen table talk.” Even in the kitchen, the KGB was an ever-present threat. People were wary of bugs and hidden microphones. Phones were unplugged or covered with pillows. Water was turned on so no one could hear. “Some of us had been followed,” says Grisha Freidin, “Sometimes there would be KGB agents stationed outside the apartments and in the stair wells. During those times we expected to be arrested any night.”

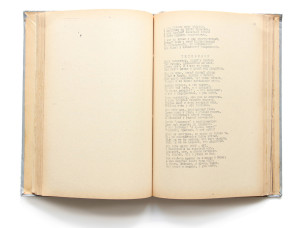

Samizdat

As the night wore on, kitchen conversations moved from politics to literature. Much literature was forbidden and could not be published or read openly in Soviet society. Kitchens became the place where people read and exchanged “samizdat.”

Samizdat collection of poems and song lyrics by Vladimir Vysotsky, published shortly after the famous Soviet bard’s death in 1980. Photo by Rossica Berlin Rare Books.

Samizdat means self published. People would type hundreds of pages on a typewriter, using carbon paper to create 4 or 5 copies. These copies were passed from one person to the next—political writings, fiction, poetry, philosophy. “Samizdat is I think the precursor of internet,” says Alexander Genis. “You put everything on it like Facebook. And it wasn’t easy to get typewriters because all typewriters must be registered by the KGB. That’s how people got caught and sentenced to jail.”

In 1973 Masha Karp’s friend got hold of a type writte copy of Boris Pasternak’s Dr. Zchivago. “She told me, ‘I’m reading it at night, I can’t let it out of my hands. But you can come to my kitchen and read it here.’ So I read it in 4 afternoons.” Alexander Genis’ family read Gulag Archipelago, by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in the kitchen. “It’s a huge book, 3 volumes, and all our family sat at the kitchen and we were afraid of our neighbor but she was sleeping. And my father, my mother, my brother, me and my grandma who was very old and had very little education — all sit at the table and read page, give page, the whole night. Maybe it was the best night of my life.”

Magnitizdat

The same thing that happened with samizdat books, happened with music. Magnitizdat, recordings made on reel to reel tape recorders. Tape recorders were expensive but permitted in the Soviet Union. Home recordings of bards, poets, folksingers, and songwriters, made and passed from friend to friend. People had hundreds of tapes they shared through the kitchens.

“My songs were my type of reactions to the events and news,” says songwriter Yuli Kim. “I would write a song about whatever was discussed. I would sing it during the discussion. If there would be someone with a tape recorder they would tape it and take it to another party. Songs were spread quickly like interesting stories.” “The most famous bard was Vladimir Vysotsky, who was like Bob Dylan of Russia,” says Alexander Genis. “That’s what you can listen to in kitchen.”

Bone Music

Before the availability of the tape recorder and during the 1950’s, when vinyl was scarce, ingenious Russians began recording banned bootlegged jazz, boogie woogie, rock and roll on exposed xray film salvaged from hospital waste bins and archives. “Usually it was the western music they wanted to copy,” says Sergei Khruschev. “Before the tape recorders they used the xray film of bones and recorded music on the bones, bone music.” “They would cut the xray into a crude circle with manicure scissors and use a cigarette to burn a hole,” says author Anya von Bremzen, “You’d have Elvis on the lungs, Duke Ellington on Aunt Masha’s brain scan. Forbidden western music captured on the interiors of Soviet citizens.”

Radio—A Window to the Freedom

Most kitchens had a radio that reached beyond the borders and censorship of the Soviet Union. People would crowd around the kithen listening to broadcasts from the BBC, Voice of America, and Radio Liberte. “It was part of our life in the kitchen,” says Vladimir Voinovich, author of The Life and Extraordinary Adventures of Private Ivan Chonkin. “It was a window to the freedom.” Voinovich’s books were circulated in samizdat and smuggled out of the country. One of his pieces was broadcast by a foreign radio station. “I heard some BBC voice reading my chapters. After that I was immediately summoned to KGB.” Voinovich was expelled from the Writers Union and later forced to emigrate.

Moscow Kitchens

Russian writer and composer Yuli Kim wrote a cycle of songs called “Moscow Kitchens” telling the story of a group of people in the 1950s and the 60s called “dissidents.” It tells how they began to get together, how it led to protests, how they were detained, and forced to leave the country. He describes the kitchen: “A tea house, a pie house, a pancake house, a study, a gambling dive, a living room, a parlor, a ballroom. A salon for a passing by drunkard. A home for a visiting bard to crash for a night. This is a Moscow Kitchen, ten square meters housing 100 guests” “This is how this subversive thought grew and expanded in the Soviet Union,” says Yuli Kim, “beginning with free discussions at the kitchens.”

Back to top [vc_column width=”1/1″][/vc_column][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][symple_divider style=”solid” margin_top=”20px” margin_bottom=”20px”]

Dissident Kitchen Recipes

[symple_tabgroup] [symple_tab title=”Pickled Mushrooms “]

Pickled Mushrooms

Ingredients:

- 3 pounds small button mushrooms, cleaned and stemmed (use the stems for another purpose)

- 1/3 cup sunflower or vegetable oil

- 1/3 cup cider vinegar

- 1/3 cup red-wine vinegar

- 1 tablespoon salt

- 2 or more minced garlic cloves

- 2 bay leaves broken into small pieces

- 1 tablespoon chopped dill or parsley

- 1 large onion sliced into thin rings

Preparation:

Place oil, vinegars, garlic, parsley and onion into a large nonreactive (nonmetallic) saucepan and bring to a boil. Add salt and stir until dissolved. Cool to lukewarm. Meanwhile, sterilize jars and lids. Place prepared mushrooms into jars. Pour brine over mushrooms and fill until 1/4 inch from the top of the jar. Cap with sterilized lid and refrigerate for 24 to 72 hours. Serve chilled.

[/symple_tab]

[symple_tab title=”Sour Cabbage“]

Sour Cabbage

from a Taste of Russia by Darra Goldstein

Ingredients:

2 pounds white cabbage

1 large carrot, scraped

1 large tart apple, peeled and cored

1 tablespoon salt

2 small bay leaves

8 whole black peppercorns

8 allspice berries

1⁄4 teaspoon caraway seed

1⁄4 teaspoon dill seed

Thinly sliced onions

Sugar

Vegetable oil

Preparation:

Shred the cabbage, carrot and apple very finely. (This is most easily done in a food processor.) Put the shredded vegetables and apple in a large bowl and sprinkle with the salt. Let stand for 1 hour, then squeeze the juice out through a strainer, reserving it. There should be 1 3⁄4 cups of expressed juice. Place one fourth of the shredded vegetables in a 1-quart jar. Top with half a bay leaf, 2 peppercorns, 2 allspice berries, and one fourth of the caraway and dill seeds. Cover with more shredded veg- etables and apple and continue the process until there are 4 layers. Pour the reserved juice over the layered cabbage, which it should cover. Cover the mouth of the jar with cheesecloth and let stand at room temperature for 4 days. Then cover the jar and refrigerate until ready to serve. To serve, cut a few thin slices of onion. Toss each portion of sour cabbage with some onion, a dash of sugar and a few drops of vegetable oil. 8 SERVINGS

[/symple_tab]

[symple_tab title=”Cornbread for Khrushchev“]

Cornbread for Khrushchev

from Anya Von Bremzen’s Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking

serves 6

Ingredients:

| 2 large eggs, lightly beaten 2 cups milk 6 tablespoons unsalted butter, melted, plus more for greasing the pan 1/2 cup sour cream 2 cups fine yellow cornmeal, preferably stone-ground |

3/4 cup all-purpose flour 1 teaspoon sugar 2 teaspoons baking powder 1/2 teaspoon baking soda 2 cups grated or finely crumbled feta cheese (about 12 ounces) Roasted red pepper strips for serving, optional |

Preparation

1. Preheat the oven to 400 degrees F with the rack set in the center. In a large bowl, thoroughly stir together the first four ingredients. In another bowl sift together the first four ingredients. In another bowl sift together the cornmeal, flour, sugar, baking powder, and baking soda. Whisk the dry ingredients into the egg mixture until smooth. Add the feta and whisk to blend thoroughly. Let the batter stand for 10 minutes.

2. Butter a 9 x 9 by 2-inch baking pan. Pour the batter into the pan and tap to even it out. Bake the cornbread until light golden and firm to the touch, 35 to 40 minutes. Serve warm, with roasted peppers, if desired. [/symple_tab] [/symple_tabgroup]

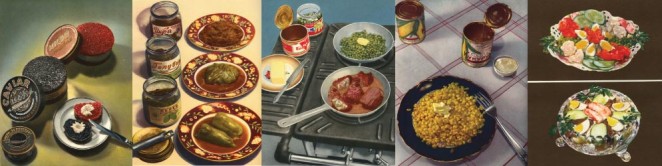

Book of Tasty and Healthy Food: Iconic Cookbook of the Soviet Union

Khrushchev and Corn

c c |

Masha Karp on the influence of corn in the Soviet

[audio:https://kitchensisters.org/audio/Web_extra_Dissident_Masha_corn.mp3] |

Back to top [symple_divider style=”solid” margin_top=”20px” margin_bottom=”20px”]

Humanists & Scholars

For additional academic references, please see the following publication:

Yurchak, A. “Suspending the Political: Late Soviet Artistic Experiments on the Margins of the State.” Poetics Today 29.4 (2008): 713-33.

McMichael, P. “‘After All, You’re a Rock and Roll (At Least, That’s What They Say)’: Roksi and the Creation of the Soviet Rock Musician”

Komaromi, Ann. “Samizdat and Soviet Dissident Politics.” Slavic Review, Spring 2012.

Back to top [symple_divider style=”solid” margin_top=”20px” margin_bottom=”20px”]

Music

Songs from the Dissident Kitchens

Extras

Poetry in the Dissident Kitchens

You and I will sit for a while in the kitchen,

the good smell of kerosene, sharp knife, big round loaf –

Pump up the stove all the way.

And have some string handy for the basket, before daylight,

to take to the station where no one can come after us.

– Osip Mandelstam, 1931

[symple_divider style=”solid” margin_top=”20px” margin_bottom=”20px”]

Links

|

||||

| For More on Bone Music http://bujhm.livejournal.com/381660.html |

LavkaLavka http://lavkalavka.com/en |