Subscribe to the podcast: iTunes | Stitcher | RSS

Our show today is in honor of the beloved poet C. D. Wright, who unexpectedly passed away recently. We were fortunate to spend time with her just a few months back at the Center for Documentary Studies where she read from her book “One With Others” which received a National Book Critic Circle Award. C. D., born in the Ozark mountains of Arkansas, was a professor of literary arts at Brown University. She is a recipient of a MacArthur fellowship, a past poet laureate of Rhode Island, an author of over a dozen books—among so much more.

The New York Times wrote: “Her work—characterized by linguistic experimentation, stylistic innovation and an ever shifting thematic canvas—was rooted in her southern heritage yet, at the same time utterly beyond category.” Like C.D. herself.

We interviewed C. D. in 2009 as part of a story we produced for our Hidden World of Girls series on NPR–and like with all of our stories—there are hours and hours of tape behind every minute of what you hear in the final piece.

So today we’re going to play our original story—a story of family, crime and the power of art to grapple with the unimaginable—and then we’re going to let it roll. To hear C. D. read from her work, and talk about life, poetry and her longtime collaboration with Deborah Luster.

A story of family, crime and the power of art to grapple with some of society’s hardest issues.

Produced by The Kitchen Sisters

In collaboration with Nathan Dalton

Mixed by Jim McKee

“My mom… It’s hard to talk about your mom. She was very glamorous but she never put on any airs. There was no saditty with her. She was infected with that southern ancestor worship thing, all into the arts of dress and manners and home and the table, conversation and story telling. She was a shutterbug.

“IN OUR FAMILY, THE CAMERA WAS MANNED BY A WOMAN”

Deborah Luster’s mother and father divorced when she was a baby and she went to live with her grandparents in Arkansas. She and her mom communicated through photographs. “If I got a new coat I would have to be photographed and usually I didn’t want to be photographed so it would be the back of the coat. There would be photographs of me and my cat, my grandfather and me.”

From her mother, Deborah would receive posed photographs. “She would dress up even when she was cooking. Designer clothes and high heels. I mean, she’d wear a mink coat to a tractor pull, think nothing of it. Red hair. Big glamourpuss.”

APRIL 1, 1988

On April 1, April Fools Day, 1988, Deborah’s mother was murdered in her bed by a contract killer who came in through her kitchen window, down her hall and shot her five times in the head. Deborah believed she had seen the man at one time so she reasoned that he might be after her as well. For seven years she lived in terror until they arrested the man and he was tried and convicted. They have never, however, caught the person who hired her mother’s killer.

After her mother’s death Deborah started to photograph. “My mom had photographed constantly, my grandmother had photographed and constantly documented our family. Photography became something that I could think to do to try to dig out of the place I had found myself.”

“Perhaps I was channeling my ancestors in the years following the deaths of my mother and grandmother. Perhaps it was their spirits that moved me to pick up a camera—for in our family, the camera was manned by women. It was my turn. Or perhaps I picked up the camera out of desperation. I did need a tool. I was buried under the loss of my family members. The world was a sinister one. I was awake and numb and frightened. How could I sleep under the same stars as my mother’s murderer? I used the camera to dig out. I found that I was still capable of making contact”.

“THERE SEEMED TO BE A LOT OF PRISONS”

Deborah had moved to Monroe in northern Louisiana. In 1998 she was sent out with other photographers by The Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities to photograph in the region in support of an empowerment zone application for the state’s very impoverished.

“Debbie started noticing that the landscape was fairly emptied out,” remembered poet C.D. Wright, Deborah’s friend and collaborator. “Then she noticed that it was fairly emptied out but for the fact that there seemed to be a lot of prisons. And she thought, ‘well maybe that’s where everybody is.” Which, in fact, is where everybody is.”

On a Sunday afternoon Deborah knocked on the gates of a small prison on the banks of the Tensas River. The warden came out and she asked if she might photograph some of the inmates there. He said yes.

“I photographed there once and realized it was a project I had been looking for for a long time, something in response to the murder of my mother,” said Deborah. “It was like it lifted when I went in through the gates it became something else.”

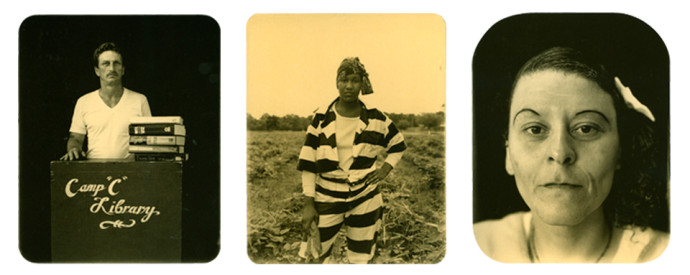

“I CAME TO PHOTOGRAPH THAT PERSON, NOT THAT PERSON IN PRISON”

Deborah got entrance to the women’s prison in St. Gabriel, the minimum security male prison in Transylvania and Angola Maximum Security prison in Louisiana. She teamed up with her long time collaborator, C.D. Wright and the two began working together on the project.

Deborah started taking very straightforward formal portraits. “I would say to the prisoners, you’re an invisible population, and this is your opportunity to show the world who you are, to present yourself to the world as you would be seen. One man went in and came back out and he had written the world “freedom” on a piece of notebook paper.”

Deborah started taking very straightforward formal portraits. “I would say to the prisoners, you’re an invisible population, and this is your opportunity to show the world who you are, to present yourself to the world as you would be seen. One man went in and came back out and he had written the world “freedom” on a piece of notebook paper.”

For the most part, the inmates posed themselves. They might want to hold something like a box of valentine candy or a family photo. One woman wanted to hold her shoe.

Deborah would take in a few pieces of black velvet and some duct tape, find a place that had good light and tape up her backdrop. She didn’t want any sort of sign of prison life. “I didn’t want that to get in the way of the person I was photographing. What I came to photograph was that person, not that person in prison.”

“I was trying to photograph as many inmates as I possibly could, because I wanted to really show the numbers of people who are incarcerated, to try to communicate to some degree, just how many y of our population reside in prisons.”

At Angola, Deborah photographed prisoners in the cotton fields where they still pick cotton by hand.

At Angola, Deborah photographed prisoners in the cotton fields where they still pick cotton by hand.

While Deborah photographed, CD Wright would interview and observe. One poem she wrote was inspired by overheard conversations on the field line—an entry level job at Angola State Penitentiary where prison farm laborers make about eight cents an hour.

LISTEN: C.D.Wright-Overheard in the Field Line

[audio:https://kitchensisters.org/girlstories/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/Web-CD_Wright-Overheard.mp3|titles=CD Wright-Overheard in the Field Line]“IN LOUISIANA EVERYTHING FEELS LIKE A COSTUME…”

Deborah photographed the women at their Mardi Gras celebration and at the Halloween haunted house at at San Gabriel women’s prison. “There were all of these traditional Louisiana costumes and archetypes,” said Deborah. “Alligator Girl, Rat Face. They run this haunted house in the gymnasium. There’s the snake room, the bird room, the bat room. And there’s the execution chamber where one inmate sits in an electric chair, and the other inmate is the executioner, and she throws a switch, and this strobe light goes on behind the head of the woman that’s supposedly being executed, and that woman starts jumping around. There’s a lot of black humor there.”

The women make their costumes out of sheets, table clothes and available materials. “The winning costumes were big striped uniforms,” said CD Wright. “Uniforms with big tall Dr. Seuss like striped hats. They were made from uniforms of the women in maximum security who could not participate in either Halloween or Mardi Gras. So those were made in their honor.”

“In Louisiana, everything feels like a costume,” said CD Wright. “The inmates had different uniforms for all of the different positions in the prison. The prisoners were identified by their work detail uniforms. People in culinary arts wore big baker hats and white jackets.”

“This man who is scarred so badly, we heard that his brother threw a tire over his head and set it on fire,” explained CD Wright. “He was so dignified. He was beautiful, really. He had green eyes. He always looked absolutely, directly at the camera. I found him very striking. Not just because he was so scarred, but because of the dignity he brought to his very disfigured face.”

The photographs are done on aluminum photographic plates reminiscent of tintypes. The aluminum is treated with gelatin silver as you would treat a canvas with gesso before you paint on it. Deborah makes paper copies of the aluminum plates for the prisoners. They are not allowed to have sharp metal objects. The photographs are small, only a little larger than a postcard. “I wanted to preserve the intimacy of these very formal photographs,” Deborah said.

THEY MADE THEMSELVES SO VULNERABLE TO ME

At Angola where 90 percent of the men that go there, die there, it was very sober. There was no clowning around. It was a very formal. The way they would pose themselves was very sort of nineteenth century.

At Angola where 90 percent of the men that go there, die there, it was very sober. There was no clowning around. It was a very formal. The way they would pose themselves was very sort of nineteenth century.

“For the most part they presented themselves as they wanted to be presented, looking out,” said CD Wright. It as was all voluntary. She returned a portion of the funds that she received from selling the plates which are on aluminum to the prisoners fund. With which they buy popcorn and books and undershirts and personal items.

Deborah made prints for each person she photographed. She returned 25,000 prints to inmates.

At one point Deborah was walking down the block at Angola, in the middle of the 18,000-acre prison, near one of the dormitories there. And a voice behind her said, “You’ve been to the women’s prison at St. Gabriel, haven’t you?” And she said, “Now how would you know that?” And the man said, “Because I sent my girlfriend a picture you took of me, and she sent me one back just like it.” “So there were these little images are flying between the prisons,” said Deborah, ” and, I thought that’s what it was all about.”

“They made themselves so vulnerable to me and it’s not often that you have an encounter like that. I know a lot of it was that they were actually posing for the people that they loved, their husbands, their wives, their children.”

“There was a woman who asked to be photographed,” said Deborah. “She said ‘I’ve been here 15 years. I’m down for 99 years. I have 19 children. My children haven’t spoken to me since I came to prison. Perhaps if I had some photographs I could send them it would soften their hearts to me.’ A few months later she said, ‘Four of my children came to visit me. The baby came and he’s nineteen. He was five years old when I came to prison.'”

SOMETHING MY MOTHER WOULD HAVE DONE

“For me,” said Deborah. “It became this project about the importance of the personal photograph, and what that little slip of paper, or piece of tin can mean to a person.”

“I think this project is the kind of thing my mother would have done,” said Deborah. “She had this way of looking right through the veneer, right into people. She could see the bottom in people. She liked to photograph her family, the food on your plate, you brushing your teeth. She photographed what she loved and that’s what she loved.”

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

How We Found this Story

We have been thinking about this girls series for a long time, even while we were in the middle of the Hidden Kitchens project. One of our central methods is to say everything out loud, tell everyone we know and don’t know about what it is we’re working on and looking for. We have a good nose for stories, but sometimes the people we know have an even better one. This story, “Deborah Luster: One Big Self” came to us because one night writer Michael Ondaatje and his wife, writer Linda Spalding were asking what new story we were working on. We described a new project we were just beginning to imagine about the secret life of girls around the world. Michael jumped in, “One Big Self. You have to see it. You have to know about Deborah Luster and her photographs and her collaboration with her C.D. Wright, the poet. They call it “One Big Self.” He told us Deborah’s story and we were mesmerized.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

“AMERICA IS A THEME PARK OF VIOLENCE…” C. D. Wright

Poet CD Wright was a long-time friend and colleague of Deborah Luster who collaborated with her on One Big Self. Here are some excerpts from her interview.

Can you talk about your collaboration with Deborah Luster?

Deborah and I met at the University of Arkansas. I was a teaching assistant and she was a senior undergraduate, so we’ve known each other for some time. We have similar sensibilities, the same kind of edgy sense of humor and the same sort of political orientation. And we have complimentary aesthetics. We’ve worked on several projects together. Both photographers and poets are used to working in solitude so it’s sometimes testing to try to work out certain visions, but our visions are actually very compatible.

This project was initiated by Deborah who is working out a long term relationship to violence which began with her mother’s murder. She’s trying to include every point of view. This is a very sympathetic project for someone who is a survivor of such a violent act. The decision from the beginning was to photograph inmates in their whole selves, their better selves.

The title of the project comes from a sentence by Terrence Malik: “Maybe all men got one big soul where everybody’s a part of–all faces of the same man: one big self.”

The popular perception is that art is apart. I insist it is a part of. Something not in dispute is that people in prison are apart from. If you can accept that — whatever level of discipline and punishment you adhere to momentarily aside — the ultimate goal should be to reunite the separated with the larger human enterprise, to see prisoners among others, as they elect to be seen. In “their larger selves.”

LISTEN: Wright talks about writing text for One Big Self

[audio:https://kitchensisters.org/girlstories/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/web-CD-Wright-inspirations-for-poem-in-One-Big-Self-1.mp3|titles=web-CD Wright inspirations for poem in One Big Self 1]What significance do you feel these photographs had for the inmates?

In the maximum security prison, the mirrors are stainless steel, so there’s a kind of warp—your reflection is not that clear. So many of these inmates don’t see themselves for years at a stretch, they don’t see the real delineation of their faces. And time passes. I think that many of them are not aware of the details of their physical changes.

The last photograph for many of these prisoners is their mug shot. In Deborah’s photos prisoners presented themselves as they wanted to be presented, looking out. Dressed in costume, holding up a sign, a photo or something they cared about.

Family portraiture, is a big tradition in the south, so these photographs were another opportunity to be included in that tradition. It was important that they were posed and dignified pictures. We tried very hard not to idealize people there; most of them were not there for spitting on the sidewalk, they had done really bad things. Most of them had brought some harm of some kind to somebody else.

LISTEN: Wright reads from One Big Self

[audio:https://kitchensisters.org/girlstories/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/Web-CD-Wright-Poem-The-Count.mp3|titles=Web-CD Wright-Poem-The Count]MORE POEMS FROM ONE BIG SELF:

If I were you:

Screw up today, and it’s solitary, Sister Woman, the padded dress with the food log to gnaw on. This is where you enter the eye of the far. The air is foul. The dirt is gumbo. Avoid all physical contact. Come nightfall the bugs will carry you off. I don’t have a clue, do I?

_______________________

they sit on the slab walk, smoke and talk

They pass a stuffed bunny from hand to hand

for their turn in front of the camera

The church ladies are out on soul patrol

they’ve got ditty bags for the prisoners

Poster: Black History, women’s prison

The blacker the college

The sweeter the knowledge

Navy is housekeeping

Khaki is for peer tutor

The search for Molly is forty-five days old

If you were a felon

You’d be home now

Cradle my head Sister

until the last rivet of grief is secure

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————

One Big Self was produced by The Kitchen Sisters, Davia Nelson and Nikki Silva in collaboration with Nathan Dalton and mixed by Jim McKee.

We’d like to thank our dear friends and sisters in collaboration – C.D. Wright and Deborah Luster. We’d also like to thank Jack Woody of Twelve Trees press, Michael Ondaatje and Linda Spalding for leading us to this story, Randy Fertel for his generous heart and support, and the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Endowment for the arts for their support of Hidden World of Girls.

C.D. Wright’s latest book is a collection of essays published in January 2016. It’s called The Poet, the Lion, Talking Pictures, El Farolito, A Wedding in St. Roch, the Big Box Store, the Warp in the Mirror, Spring, Midnights, Fire & All. Published by Copper Canyon Press.

RADIOTOPIA:

Fugitive Waves is produced by The Kitchen Sisters with Nathan Dalton and Brandi Howell.

We’re part of Radiotopia from PRX – a collective of the best story-driven, creative cutting edge radio shows on earth.

From all of us at Radiotopia, many thanks for listening, sharing these programs with your friends and supporting this new experiment in supporting storytelling.

We’d like to thank the many of you who have donated to Radiotopia and The Kitchens Sisters, especially designer and illustrator Jez Burrows, whose most recent project Dictionary Stories is a collection of very short stories entirely composed from example sentences from the dictionary. Find it at dictionarystories.com.