Subscribe to the podcast: iTunes | Stitcher | RSS

[metaslider id=4829]

“They call it ‘The Hummus Wars’ when Lebanon accused the Israeli people of trying to steal hummus and make it their national dish, hummus became a symbol,” Ronit Vered a food journalist with Haaretz, in Tel Aviv tells us. We meet her deep in Shuk HaCarmel an old sprawling street market on a rainy Wednesday afternoon. Ronit writes about the history and culture of food in Israel.

Fadi Abboud, born in Lebanon, served as Minister for Tourism there from 2009 to 2014. Mr. Abboud was the man who led Lebanon to break the Guinness World Record by making the largest tub of hummus in the world. At the time Abboud was also Chairman of the Industrialists Association. “A group of us just came from a food exhibition in France. There they were telling us that hummus is an Israeli traditional dish. I mean the world now thinks that Israel invented hummus. I was rather upset you know and I thought the best way to tell the world that the hummus is Lebanese is to break the Guinness Book of Records.”

Fadi Abboud

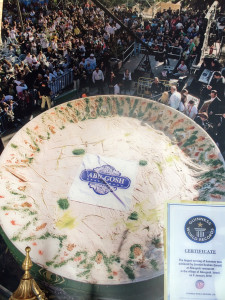

At the ceremony, when Guinness awarded Lebanon the prize for it’s 4,532 pound plate of hummus, Fadi announced “We want the whole world to know that hummus and tabouli are Lebanese and by breaking the Guinness Book of World Records the world should remember our cuisine, our culture.”

“It was big issue, all over the news, that hummus was Lebanese. I said, ‘No, hummus for everybody.” That’s Jawdat Ibrahim, owner of Abu Gosh Restaurant in Abu Ghosh village between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. “I hold a meeting in the village and I say ‘We are going to break Guinness Book of World Record.’ Not the Israeli government, the people of Abu Ghosh.

Within months this news was broadcast round the world. “In the town of Abu Ghosh this morning Israel re-took the title for the World’s Largest Hummus Dish weighing four tons and served in a satellite dish.”

“Yes”, said Jawdat, “a satellite dish. It’s a dish, no? Media, they came here. Over 50 TV channels all over the world. More than Obama visit in the country.”

Ronit Vered has been thinking about these issues for years. She tells us in Israel there is not a strong food tradition, the country has only existed 60 years. There were not specific dishes that were common ground for all the Israelis. So hummus became a common ground. “Palestinians also made hummus a symbol,” says Ronit, “that we didn’t only take their land, we take their food as well and made it ours.”

Counter attack: On Jan. 8, 2010, the Arab Israeli village of Abu Gosh served up this giant satellite dish full of hummus, weighing over 4 tons — about twice as much as the previous record set by Lebanon just months earlier.

Alessio Romenzi/AFP/Getty Images

“The hummus is our tradition. Tabouli is our tradition. They take our hummus and they make it their tradition.” So says, Nuha Musleh a Palestinian woman who works as a fixer with international journalists and owns a rug and antique store in Ramallah. After a long line crossing the checkpoint from Jerusalem to the West Bank and Ramallah, Nuha stops her SUV at one of her favorite restaurants so we can taste Palestinian hummus. “Now we are in Ramallah. People run to get hummus when they are in Ramallah. It’s like getting a good pizza in downtown Rome. Or getting a good T-Bone steak in Texas, I imagine. I haven’t been.”

The restaurant owner leads us into his kitchen, where plates of hummus piled with radishes, pickles and sumac are being made. He begins to tell us what makes his hummus so distinguished. Nuha translates. “What distinguishes any hummus from another is nafs – which is soul in Arabic. Here, they pound it! They don’t use a machine. They use good tahini, sesame seeds crushed, sumac, lemons from Jericho. Olive oil from the Hebron hills.” He tells us Palestinians don’t mind that Lebanon is proud of its hummus, that Egypt makes hummus. It puts Arabs together.

Fadi Abboud has been studying the history of hummus for some time now. “The word ‘chickpea’ in Arabic is hummus. So the actual name comes from the Arabic for chickpea.” Fadi told us Lebanon tried to register hummus with the European Union with a protective Designation of Origin in the same way champagne is registered by France, parmesan by the Italians, and the Greeks lay claim to feta cheese. Fadi was asking the EU to ban the use of the word hummus by any other country than Lebanon. The Association of Industrialists called this campaign “Hands Off Our Dishes.”

Ari Ariel, Assistant Professor of Gastronomy at Boston University and author of the article “The Hummus War” has been following the battle for years now. He said part of the problem from the Lebanese perspective was most of the pre-packaged hummus in the world was being sold by Israeli companies.

In the end, the EU did not allow Lebanon to register the word “hummus” for their own.

Ronit Vered has chronicled the arc of Israeli food and cooking for years. It’s as thorny as all issues connecting the Israelis and the Palestinians. “In the first two decades of the state the Israeli people didn’t eat really eat local food. They stuck to their old habits the thing that is close to your heart. It’s also a political issue. If I eat Palestinian food in a way I acknowledge that they exist, that there are other people here who have food of their own.”

After years of resisting local food, by the 1950s the Israeli Army started serving hummus in mess halls. Soon the average Israeli came to know hummus as an everyday food. Dafna Hirsch lives in Tel Aviv and is a faculty member at Open University of Israel and author of the article “Hummus is Best When it is Fresh and Made by Arabs.”

Dafna tells us that as these food becomes more familiar to the European settlers, hummus became hip, something young people began to eat. Hummus became appropriated as the food of the new Sabra, the Israeli new man, who is rooted in the land, wears the Kofia and eats hummus and falafel.

“In Israel hummus is considered a masculine dish, says Dafna, “It a kind of masculine ritual to go with a group of men to the hummusiya and eat hummus wiping with these large circular gestures.

Hummus has a natural community because it is not merely a dish but more like a subculture. So says Shooky Galili, a young entrepreneur who lives in Tel Aviv and has a blog about hummus, Humus101.com. “I have many people who want to know about out the new places, ‘I’m in Jerusalem, where do I go?’”

Nuha is far from taken with the subculture Shooky and many Israelis are feeding. “Hummus, unfortunately, has become in the category of fast foods. But actually in Arab and all of Palestine hummus is a Friday honorable breakfast. The father wakes up in the morning, makes hummus, makes food. Invites all his daughters and daughters-in laws and sons. It’s a way to get together in the morning of a Friday. When the family wants to throw all their worries and problems away.”

Nuha is driving us back to Jerusalem, back towards the checkpoint. Once again we are in a long wait in a long line of vehicles. I notice the food vendors and rug merchants who have set up makeshift businesses along the crawling route. This is Nuha’s daily route and she’s got it wired. “As we approach the checkpoint there’s usually congestion because there’s the refugee camp on left, a village called Qalandia on the right and there’s no man’s land Kufr Aqab. You have 130,000 people using one road. I never think of eating breakfast when I have to go through the checkpoint. There’s a kabob stand and there’s a ka’ak vendor, the bread with sesame and za’atar. It’s a big business. Because you’re stressed you need something. You could get shot. The checkpoint could close. You could get a gas bomb. Suddenly you’re not a human being. The kitchen of the checkpoint is really crucial to connect people together as human beings.”

Back in a cab in Tel Aviv, I notice the tattoo on my taxi driver, David Varon. “What does your tattoo say?” “No Fear” says David. “You cannot live in fear in Israel. Some people are afraid to live in a country where there is so much blood and wars and conflict over thousands of years. This conflict is about religion and it will not be over until religion will be over. Hummus and falafel, food is maybe the only thing that gets people to sit together with different thoughts to eat the same food.”

Most of the hummus makers at the old hummusiyats – Lena’s in Jerusalem, Abu Hassam in Tel Aviv, Said in Akko all echoed David’s thoughts. But Dafna Hirsh isn’t buying it. “This kind of approach which says ‘Oh if we eat together peace will come through the stomach. But no. As long as colonization continues, as long as occupation continues then hummus is not going to solve it. That sentiment echoed at Tony Rami’s Falamanki and Le Professeur in Beirut as well.

Still Jawdat Ibrahim, who grew up in poverty in Abu Ghosh, an Arab living in an Arab village in Israel, came to America in his early 20’s with a quarter in his pocket, won the lottery in 1973 in Chicago and won $23 million dollars and returned to his village in Israel to open the hummus restaurant we are talking in, has a vision. A kitchen vision. “We broke the Guinness Book of World Records, but to make hummus is not the issue. To put people together, that is the main thing. People talking about blood and killing and I want to take to different way. People can talk about the Middle East about nice things, not killing and shooting. Hummus. Nobody get hurt with this war.”

Post Script: Currently Beirut is back on top in The Hummus Wars with the 23,042 pounds of hummus they prepared displayed on the world’s largest ceramic plate.

News coverage of the “Hummus Wars” from JPOST – World News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Special Thanks: In Lebanon: Kamal Mouzawak, Fady Abboud, Jihane Chahla, Sami Moussallem, Souk el Tayeb, Tawlet, Andre Abi Awad, Beit Douma, Beit al Qamar, Lara Shabb, Peter and Nathalie Hrechdakian, Jackson Allers, Barbara Massaad, Colette Naufal, Beirut International Film Festival, Le Professeur, Maya Zbib, Tony Ramy, Jihane Khairallah and Hotel Albergo Relais & Chateaux, Myriam Shwayri, Soufra at the Burj al Ba Rajneh refugee camp, Chez Maguy, Marc Codsi, Bachar Mar Khalife. In Ramallah: Nuha Musleh. In Israel: Mishy Harman, Maya Kosover, Shoshi Shmuluvitz, Rachel Fisher, Yochai Maital, Benny Becker and the team at Israel Story, Jawdat Ibrahim, Ronit Vered, Dafna Hirsch, Shooky Galili + Hummus 101, Ben Lang + International Hummus Day, David Varon, Sophie Schor, Oren Rosenfeld, Sami at Abu Hassam, Lina Hummus, David Ben Shabbat, Efrat Shagal & Peace of Cake, Erez Komorofsky, Elisheva Goldberg, Kamel Hashlamon, Ra’anan Alexandowicz, Hummus Abu Shakra, Hummus Askandar, Maya Zinshstein, Naama Shefi & EatWith, David Ben Shabbat, Kobi Tzafrir and Hummus Bar at M Mall in Kfar Vitkin, Rafram Hadad, Manta Ray Restaurant, Michas Hummus. In The US: Ari Ariel, Emily Harris, Yotam Ottolenghi, Margaret Rogalski, Third Coast Audio Festival, Robb Moss, Mark Danner, Tom Luddy, Sandy Tolan, Dore Stein, Johanna Mendelson Forman, Laila el-Haddad, John Lyons.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_row][symple_divider style=”solid” margin_top=”20px” margin_bottom=”20px”]

RECIPE TITLES

[symple_tabgroup]

[symple_tab title=”Yotam Ottolenghi’s Hummus“]

from Jerusalem: A Cookbook

for more information visit http://www.ottolenghi.co.uk/

INGREDIENTS

- 1 ¼cups dried chickpeas (250 grams)

- 1 teaspoon baking soda

- 1 cup plus 2 tablespoons light tahini paste (270 grams)

- 4 tablespoons freshly squeezedlemon juice

- 4 cloves garlic, crushed

- Salt

- 6 ½ tablespoons ice-cold water (100 milliliters)

PREPARATION

- Put chickpeas in a large bowl and cover with cold water at least twice their volume. Leave to soak overnight.

- The next day, drain chickpeas. In a medium saucepan, combine drained chickpeas and baking soda over high heat. Cook for about 3 minutes, stirring constantly. Add 6 1/2 cups water and bring to a boil. Cook at a simmer, skimming off any foam and any skins that float to the surface, from 20 and 40 minutes, depending on the type and freshness. Once done, they should be very tender, breaking easily when pressed between your thumb and finger, almost but not quite mushy.

- Drain chickpeas. You should have roughly 3 cups (600 grams) now. Place chickpeas in a food processor and process until you get a stiff paste. Then, with the machine still running, add tahini paste, lemon juice, garlic and 1 1/2 teaspoons salt. Slowly drizzle in ice water and allow it to mix for about 5 minutes, until you get a very smooth and creamy paste.

- Transfer hummus to a bowl, cover surface with plastic wrap, and let it rest for at least 30 minutes. If not using immediately, refrigerate until needed, up to two days. Remove from fridge at least 30 minutes before serving.

[/symple_tab]

[symple_tab title=” Pickled turnip & beetroot “]

from Jerusalem: A Cookbook

Makes 1 large jar, approximately 1.5-2 litres

INGREDIENTS

10 small or 5 large fresh turnips (1kg in total)

3 small beetroot (240g in total)

1 green or red chilli, cut into 1cm slices

3 tender celery stalks, cut into 2cm slices

300ml distilled white vinegar

720ml warm water fine sea salt

[/symple_tab][symple_tab title=” Falafel-Gaza style“]

from Laila El-Haddad’s The Gaza Kitchen blog

INGREDIENTS

Put through a food grinder or pulse in food processor in batches, starting with chickpeas:

2 cups dry chickpeas, rinsed and soaked in water for 16 hours

1 bunch cilantro (roughly 3/4 cup chopped)

1 bunch dill (roughly 1/2 cup chopped)

1 bunch parsley (roughly 1 cup chopped)

7 garlic cloves

5 hot green chilies, adjust based on personal preference

1 T. each: cumin, coriander, salt, and black pepper

1/2 tsp nutmeg

Set aside for 2 hours, then add immediately before frying:

1 tsp baking soda

2 T. roasted sesame seeds

Shape in small patties (dip hands in a little water if necessary to prevent sticking) or use a falafel mold, then fry in hot oil. Drain on a paper towel. Serve with tahina sauce (below), julienne onions sprinkled with 1 tsp sumac, sliced tomatoes, chili paste (filfil mat’hoon) and assorted pickles.

Tahina Sauce:

Blend together until smooth:

2 T. Tahina

1/2 cup water

Juice of two fresh lemons

1 garlic, mashed

1/2 tsp salt

[/symple_tab]

[/symple_tabgroup]

Back to top

[symple_divider style=”solid” margin_top=”20px” margin_bottom=”20px”][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Humanists & Scholars

Ari Ariel, PhD

Assistant Professor of Gastronomy

Boston University

excerpt from Ari Ariel interview

The Hummus Wars is a conflict that took place on two different fronts. A few years ago, Guinness World Records began traveling back and forth from Israel to Lebanon and the United States to measure the largest dish of hummus in the world. The first Guinness World Record attempt is in May 2008 in Jerusalem, and it’s an 882 pound dish made by a group of chefs sponsored by Sabar, an Israeli food company. A few years later, a group of Lebanese chefs decided they should take the title and made a 4,532 pound dish. Soon after, a group of Israeli chefs in the village of Abu Ghosh made a dish of hummus that was about 9,000 pounds and then finally, in 2010, the student chefs from Al-Kafaat University in Lebanon prepared what is now the current largest dish of hummus which is 23,000 pounds.

This is an interesting place where nationalism enters into this conflict over food; it bothered the Lebanese chefs as an aspect of the Arab-Israeli conflict and the Israel-Palestine conflict. They thought of hummus as a traditional Arab food. Israel claiming this world record was a way of Israel stealing hummus from the Arab community. Hummus, the word itself, is the Arabic word for chickpea.

[read more=”Read more” less=”Read less”]

Since 1992, the European Union has had these some these food schemes so that you could register a food and get a trademark on it as a way to preserve specific local food ways. There are three schemes: one just requires that you’re using traditional methods in preparing a dish, a second one requires that at least part of the dishes prepared in a particular area and the most coveted one really requires that the entire dish or the entire product is made in a particular area using traditional ways. A group called the Association of Lebanese Industrialists started a campaign called Hands Off Our Dishes. It was an attempt to get Israel to stop producing hummus. They tried to trademark the terms “hummus” and also things like “baba ganoush” or “tahini” the same way that something like “Parmesan Reggiano” is a trademark in Europe. They were hoping to get a trademark for hummus so that only they could package it as a prepared food, but their legal case was so bad that they dropped it.

In addition to the aspect of nationalism and the Arab-Israeli conflict, part of the problem from the Lebanese perspective was that there are these two large Israeli companies that were selling most of the hummus in the world, Strauss and Olsam. Strauss produces Sabra, which is now the most popular packaged hummus in the United States. As part of the BDS (boycotts, divestment and sanctions against Israel) movement, people who are supportive of of Palestinian rights have attempted to boycott Sabra in particular places.

I would say that everyone in Israel eats hummus at this point. It’s a food of the entire community and communities of the country of Israel. The part of the Lebanese opposition to this is that the appropriation of Palestinian food ways is part of this continuation of a colonial process of appropriating land and culture and other aspects of Palestinian society. It appears that certain early Jewish immigrants to Palestine started adopting certain Arab behaviors and certain Arab food ways as a way to mark themselves as indigenous and to experience a local authentic lifestyle as part of their migration process, so they started eating hummus at the beginning of the century and it became more common in the Jewish communities. By the 50s, the Israeli army was serving hummus in mess halls and things of that nature.

More recently there are attempts in Israel to look for some sort of authentic hummus, even in problematic ways. You get the impression sometimes that what people are looking for is really an old man or woman in a village someplace making hummus with a mortar and pestle and they might hold that up as the most authentic. It’s part of culinary tourism, and part of the search for traditional ingredients and traditional dishes that we seem to have become a little bit obsessed with.

There’s a big debate in the food studies literature about and maybe in the popular literature more generally about whether food can be a source of a way to bring people together. In the case of the hummus wars, things are spoken about as if they’re really a military conflict. The hummus wars have become the front in the Arab-Israeli conflict. The terminology used is often military. There’s a quote in the article**, “Lebanon is denied smoothing the passage of hummus through the country” and says “there is no discernible buildup of the chickpea derived substance on the southern boredom border with Israel.” If food and national identity are universally linked, here political dispute and warfare produce a rhetoric of violence that transforms cooks into combatants.

This is an issue of hummus being connected to identity. For example, you get a sense that Odysseus, when he’s looking for people who are civilized, is looking for people who eat bread. This is true in the Bible as well; there’s way in which historically, food has always marked a difference between us and some other group. What we eat marks who was acceptable in our group and who’s not and these hummus wars are a continuation of that trend.

**Ariel, A. (2012). The Hummus Wars. Gastronomica: The Journal of Food and Culture, 12(1), 34-42. doi:10.1525/gfc.2012.12.1.34

[/read]

Dafna Hirsh, PhD

Professor of Sociology

The Open University of Israel

excerpt from Dafna Hirsch interview

In Arab society, hummus is a traditional dish, it’s something that women were producing at home long before it became commercial. Jews became acquainted to it through restaurants and more public institutions. But mostly, hummus entered [Jewish] homes through the industrial version.

We know for sure that in the 19th century, hummus was produced and consumed in Palestine when there was still a very very small Jewish community, mostly of European origins, most of which probably did not consume hummus. When European Jews began to settle in Palestine, the majority would look at Arab food with suspicion, sometimes even disgust. Gradually in the 1950s the food became more familiar to the the European settlers. It becomes kind of hip, something the young people will eat, and it’s appropriated by some of the cultural tone setters as the food of the new Sabra, the new men, the kind of men rooted in the land, who eat hummus and falafel. Then the big breakthrough is in the late 50s when it becomes industrialized and widely consumed.

[read more=”Read more” less=”Read less”]

The discourse of origins is something that is pretty recent. I find once in a while people talking about this issue of culinary appropriation and the way that these dishes are just appropriated then defined as Israeli national food. Hummus is actually first marked as a national food by the food industry, by Telma. The Israeli industry in general has an interest in forging a kind of national culture and national cuisine. During the 1960s and late 1950s, hummus gets shipped to all kinds of Israel weeks abroad and Israel exhibitions. This is the first context when these dishes are being defined as as national food, but gradually the discourse changes and Arab hummus is defined as the best and most authentic. You have all kinds of culinary experts and gourmets and food writers going on and on about the wonders of Arab made hummus. This is something that that involves a lot of commercial interests.

Hummusiya, hummus joints, are usually simpler restaurants. If they were too fancy people would most likely avoid them because the whole point is that [hummus] is considered simple food. You will seldom see a group of women sitting together in a hummusiya. It’s considered a kind of masculine ritual to go with a group of men to the hummusiya and what is called “wipe” in Hebrew. “To wipe” is like a slang for eating hummus with a piece of pita bread off the plate, so whereas Arabs will say “to dip,” meaning holding the pita as a kind of spoon and lifting the hummus to your mouth with the peta, in Hebrew wiping became the slang word for eating hummus with this large circular gesture.

In Palestinian society, hummus places were masculine spaces. Hummus is considered a masculine food because of the gestures involved in the consumption of it. It’s not something you eat gently, it’s heavy food. Working men would go in the middle of the day, or sometimes for breakfast because hummus would hold them for hours. There is a line of representations going all the way back to the early Zionist settlers who saw the Arab workers as the epitome of masculine men, able-bodied, good-working men. The whole performance of consuming hummus has to do with establishing yourself as a native to Palestine, and someone who consumed the local dishes. [Hummus consumption] has whole bundle of meanings associated with native status, masculinity.

So often it’s regarded as as a case of culinary colonialism. I want to complicate this perspective because it’s not just that when people want your land, they will want your foods. It often doesn’t work like that. Often the settlers’ attitude towards the foods of the indigenous people is the complete opposite, they are disregarded. So another interesting thing for me is to see how it happens as a social process, why people started to consume hummus and how it’s consumption pattern changes over time. This kind of appropriation of Arab dishes is definitely related to the process of colonization, but if you look at the history of consumption of hummus and the way people think and talk about hummus, you see it’s not entirely parallel to the political process and political changes.

[/read]

For additional academic references, please see the following publications:

Ariel, A. (2012). The Hummus Wars. Gastronomica: The Journal of Food and Culture, 12(1), 34-42. doi:10.1525/gfc.2012.12.1.34

Dafna Hirsch and Ofra Tene, “Hummus: The Making of an Israeli Culinary Cult”, Journal of Consumer Culture 13 (2013), 25-45.

Dafna Hirsch, “‘Hummus is Best when it is Fresh and made by Arabs’: The Gourmetization of Hummus in Israel and the Return of the Repressed Arab,” American Ethnologist 38 (2011), 617-630.

Gvion, L. (2012). Beyond Hummus and Falafel: Social and Political Aspects of Palestinian Food in Israel (California Studies in Food and Culture). University of California Press.

Back to top

[symple_divider style=”solid” margin_top=”20px” margin_bottom=”20px”]

Music

Bachar Mar-Khalife, Balcoon

Tomber Longtemps, Ibrahim Maalouf

Hummus Metamtem, Nigel Addmore

Fat Mobile, Arthur Oskan

Maeva in Wonderland, Ibrahim Maalouf

Be’Yom Shabbat, The Idan Raichel Project

Basalon Shel Salomon, Hadag Nahash

Back to top

[symple_divider style=”solid” margin_top=”20px” margin_bottom=”20px”]

Extras

The Israeli Story

The idea for “Operation Hummus” came to us when we recently met three young Israeli men who host the Israeli version of This American Life, at an international radio conference in Chicago. As we do with most everyone we meet, we asked what their hidden kitchen was? “What is their Israeli Hidden Kitchen,” we asked? “Hummus.” they all said. And they began to tell us about the vibrant traditions, rituals, history and controversies that center around this humble dish of chick peas, tahini, lemon juice, garlic and spices. Their stories set us on the course of this radio documentary.

We would like to thank Mishy Harman,Ro’ee Gilron, Yochai Maital and entire staff of The Israel Story, who helped us immensely during our time reporting in Israel.

To hear more stories from The Israel Story, please visit their website.

International Hummus Day & Hummus Map

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/263833367″ params=”color=ff5500&inverse=false&auto_play=false&show_user=true” width=”100%” height=”20″ iframe=”true” /]

May 13th is International Hummus Day — a day to celebrate the deliciousness of this beloved Middle Eastern spread. The basic ingredients in hummus are simple: cooked or mashed chickpeas, olive oil, tahini, lemon juice, salt and garlic; but it’s history is not. Every country, culture, and religion in the Middle East has a different twist on the recipe, which in turn has created long standing arguments about who makes it best. Both Israelis and Arabs have made a strong claim to being the original creator of hummus, and in recent years a Guinness Book of World Records inspired feud has broken out between Israel and Lebanon, known as the Hummus Wars.

Yet, May 13th is not about who owns hummus, it’s about spreading the love for this dish. Ben Lang, a tech entrepreneur who lives in Israel, created the holiday in 2013 and since then it’s spread internationally. Lang even created a global Hummus Map to help people find the best local hummus. To participate in International Hummus Day you must eat it for breakfast, lunch, or dinner…or all three. After that you can share your chickpea love in a number of ways: organize or participate in a hummus-related event; document your hummus eating on social media with the hashtag #hummusday; participate on facebook; or add your hummus place to the Hummus Map.

Back to top

Ra’anan Alexandrowicz

Ra’anan Alexandrowicz carved name recognition as writer and director of award-winning films such as the full-length feature James’ Journey to Jerusalem(Director’s Fortnight, Cannes 2003, Toronto 2003), and the documentaries The Inner Tour (Berlin 2001, Sundance 2001), and Martin (Berlin 1999, New Directors, New Films 1999, MoMA permanent collection). Ra’anan’s critically-acclaimed works have been theatrically-released to international audiences and broadcast worldwide.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/274182977″ params=”color=ff5500&inverse=false&auto_play=false&show_user=true” width=”100%” height=”20″ iframe=”true” /]

In his film The Law in These Parts, Alexandrowicz examines the legal history of Israeli’s occupation of Arab territories through interviews he conducted with a number of judges who were responsible for carrying out the orders of military commanders.

Tony Ramy

Tony Ramy is President of the Syndicate of Owners of Restaurants in Lebanon. He is the co-owner and General Manager of Al Sultan Brahim group of restaurants, which started in 1961 in Beirut.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/274184547″ params=”color=ff5500&inverse=false&auto_play=false&show_user=true” width=”100%” height=”20″ iframe=”true” /]

[symple_divider style=”solid” margin_top=”20px” margin_bottom=”20px”]

Links

|

|

|

| Humus 101 | Hummus Day |