[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/1″][vc_column_text]

RECIPES | SCHOLARS | MUSIC | EXTRAS | LINKS

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row] [metaslider id=2919]

Story #8: Hidden Kitchens Mexico — The Tequila Chamber of Commerce

[audio: https://kitchensisters.org/audio/Hidden%20Kitchens_Tequila_MIX_062014.mp3]“My name is Guillermo Erikson Sauza. We’re in the town of Tequila. We’re on the northwest slope of the volcan de Tequila. It’s an old, expired volcano. I’m the fifth generation to make tequila in my family.” Sauza, a member of one of tequila’s royal families, is giving us a tour of his 125 year-old tequila distillery, walking us through step-by-step of his tequila-making process. His distillery, and hundreds of others, both large and small fill the hills and valleys some 60 minutes outside of Guadalajara, Mexico’s second largest city.

“At our little distillery here in La Fortaleza, we only make 100% agave tequila. Cenobio Sauza, my tata abuelo, my great-great grandfather, got to this town in the 1850s when he was a 16 year old boy.” At the time Tequila was a boomtown. and a lot of people setting up tequila distilleries there. The natural spring water, the volcanic soil, the climate all made the region perfect for the growing of blue agave tequila weber as the plant is known.

“Previously it was illegal to make distilled spirits in Mexico to keep competition away from the spirits that were produced in Spain. Cenobio started the brand of Tequila Sauza in 1873, he was the first to export tequila into the United States,” Guillermo continues. In 1893 Tequila Sauza made a sensation when it was served at the Chicago World’s Fair. At that time the drink was called vino mescal.

The drink of cement workers and bricklayers

“In the early day tequila was the drink of cement workers and bricklayer’s. It wasn’t for the upper classes. We used to go to a wedding and you would see all brandy bottles on the tables. There was never any tequila bottles,” remembers Sauza. In 1946 Guillermo’s grandfather Javier took over, and slowly helped make tequila what it became, the product of Mexico.

“Unfortunately he sold Tequila Sauza when I was about 20 years old in 1976. We were all stunned. All of a sudden he just sold out. I found him reading the newspaper and I said ‘Oye Daddy Javier. Porque vendiste la fabrica?” Daddy Javier, why did you sell the distillery? And he pulled his paper to one side and he said, “Porque yo queria.’ Because I wanted to. That’s really all we ever knew of why he wanted to sell.

I think it was an issue of continuity of somebody being prepared to run the distillery. This is a very tough business.” But the family held on to one of its distilleries and about a decade ago Sauza decided to put it back together and started making tequila in the traditional way. He brought out his first brand, that in Mexico is called “Los Abuelos,” The Grandparents. In the United States it is sold under the name Fortaleza. It means fortitude.

Agave business is a casino business

It takes five to eight years for the blue agave, the only agave that can used in a bottle that has the official apellation, Tequila, to mature. And growing agave over that span takes a lot of knowledge and maintenance. So agave growers and tequila producers must be looking far ahead at all times. “Agave business is a casino business,” says David Suro, President of the Tequila Interchange Project (TIP) a non-profit organization and consumer advocacy group for agave distilled spirits comprised of bartenders, consultants, educators, researchers, consumers and tequila enthusiasts.

The organization advocates for the preservation of sustainable, traditional and quality practices in the industries of agave distilled spirits. Suro is also President of Sembra Azul Tequila, made here in the highlands of Jalisco, the state of Mexico where most all tequila comes from. Sembra Azeul has been Kosher certified in Mexico. Kosher, Suro tells us, because there is no organic certification in Mexico, and this is the closest certification he could get to let the public know his commitment to organic, sustainable agave growing and tequila-making practices. Suro is driving us further into the red-soil highlands, to the town of Arandas, to meet master distiller, Carlos Camerena, one of the most respected tequileros, tequila makers, in Mexico.

Tequila, Arandas and Atotonilco are are three of the major areas where agave thrives and exceptional tequila is made. Camarena is a third generation master distiller. His grandfather, Carlos and his sisters now run this legendary family distillery. Tapatio, Tesoro de Don Felipe and Tequila Ocho are some of the tequilas he produces at “La Altena Distillery.”

Tequila is a huge part of the future of Mexico

“Guadalajara is the Silicon Valley for Mexico in so many ways,” says Mexican video journalist Rogelio Navarro. “Tequila is a huge part of the future of Mexico. The biggest tequila companies are not Mexican anymore, they are internationally owned. Tequila produces a lot of jobs and a lot of money, and now they just the sent the first package of tequila to China, and they’re expecting to sell millions of liters of tequila in China. Tequila can produce a lot of money.

“Tequila does not only mean alcohol, it also means culture. Tequila is associated with folkloric dancing, with music, with film, with tourism. Tequila town is about 40 minutes drive from Guadalajara. Navorro often covers stories about tequila and has come to know the regulatory agencies well. “There are two main authorities when it comes to tequila, The Tequila Chamber of Commerce, which is pretty much on the tequilerosside, tequila makers side, and the Tequila Regulation Council. They are now very focused on what is happening with tequila over the world. Are we getting to the US, to India, to China? And they make sure that tequila produced in tequila county is actually tequila because of the agave they are using and the amount in the final product. I know they have problems with people outside of Mexico producing something they label as tequila, but its not tequila. It’s not even made out of agave. Tequila is like champagne. If you want to buy champagne, it’s always from France, from the Champagne region, And that’s the same that happens here with tequila. It’s got the appellation of origin.”

Imagine a field of blue pointy plants as long as you can see from you car, from the train, from the plane, and that’s the way it looks, a tequila field. The same way wine producers are always fighting the climate, the weather, the bugs, the conditions, the tequileros and agave producers are always fighting, but instead of one season of growth and then harvest, they cultivate their plants between five to eight years before the sugar levels are high enough for harvest. Navarro has been following some of the efforts to make tequila production more organic and sustainable, as it is an industry that produces a serious amount of waste. “What they are doing with the bagasse from the tequila industry, the waste that it produces as it goes through the distillation process.

The cellulosic waste, or bagasse, is what is left once you cook the agave plant and chop it and put it through a mill. They have the juice and they’re making tequila, but on the other hand what do they do with all this organic trash? They were trying to compost it, and you can use it back in the agave fields as well, but it’s easier to just throw away. So there’s a guy that decided what are people in Brazil are doing with the cane? And he bought the machines and started compressing the bagasse and making bricks, and he started to sell them as charcoal for roasting and bricks for houses.

Can you perceive the aromas?

Back at La Altena, Carlos Camerena stands in front of one of the seven massive ovens, or hornos, he has for roasting the agaves. “This is your first time in a tequila distillery right/” Can you perceive the aromas, The cooked agave. That sweet smell of honey water from the cooked agave. It attracts a lot of bees, so we are usually surrounded by bees because they get attracted by these smells. We grow and produce all our own agaves. This is one day’s harvest. The jimadors, the men who harvest the agaves, bring about 20 tons of agave per day. We’re a small distillery, making about 50,000 cases per year. Which is nothing, with let’s say Jose Cuervo that can produce six million cases a year.” We move on to a huge round pit made of stone, with a stone wheel on top of it. “What we are looking at is called a “tahona.” In the past the wheel was turned by mules. The stone crushes the agave and squeezes out the juice. Three years ago Carlos’ father pulled out the mules and replaced them with a John Deere tractor to pull the wheel. Tequila Seite Leguas about an hour away in Atotonilco is one of the last distilleries to crush it’s agave with a stone pulled by mules.

Agave Goddess

Carlos Camerena, at La Altena is also thinking about the environmental impact. We’re noticing the summers are getting hotter and hotter every year and they winters are getting colder. Traditionally it took the blue agave 8 to 10 years to mature. Now e’re looking at the agaves maturing at 5,6,7 years sold. So much hot is making the plant grow faster, but not letting it get all the nutrients from the soil and develop the sugar content and the acidity and to be as healthy. Everybody here is talking about the effect of cambio climatico, or calientamiento global, the global warning on all our agricultural products.

And of course we face some kind of difficulties as being a monoclone and actually all the plants that we use are clones from the mother because all the reproduction from the agave is non-sexual. About 8 years ago ago Camerena started thinking about not the planet he was on living in but what kind of planet he wanted to leave his kids. From that moment he started getting treating all of residues at the distilleries, all of the leftovers, instead of just dumping them in the garbage. With al the organic materials they are producing they started composing, making an organic fertilizer that they put back on our agave fields. And the distillery started recycling all the water they use instead of just throwing it away.

Carmen Villareal is a tequilera, one of the few women in Mexico to run a Tequila company, Tequila San Matais that is now 127 years old. Her It is Carmen who tells us about Mayaguel, the pre-Columbian goddess of fertility and maternity who is sort of the patron saint of tequila. She had is often pictured with 200 breasts. “Our agaves have babies,” says Carmen.

“Normally one agave can have ten or twelve babies so it is about being productive. I see Mexico as Mayaguel, with productivity and fertility and to work for the growth and wellness for our country. Wellness because the tequila industry contributes a lot the country. Mexico is a country with great poverty. Tequila is an important income for the country. For example our distillery is located in a tiny town and we are practically the only source of work in the area. The way I see the industry we we can help bring wellness and opportunity to our country.”

Back to top [vc_column width=”1/1″][/vc_column][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][symple_divider style=”solid” margin_top=”20px” margin_bottom=”20px”]

Tequila Recipes

[symple_tabgroup] [symple_tab title=”Margarita Mexicana“]

Margarita Mexicana

from Viva Tequila! Cocktails, Cooking, and Other Agave Adventures | Serves 1

Ingredients

Salt and quartered lime to rim glass, optional 1 1/2 ounces tequila blanco (or reposado) 3/4 ounce fresh lime juice, preferably from Mexican limones 3/4 ounce Cointreau

Making Mexican Margaritas

Chill long-stemmed cocktail glasses prior to serving. Pour coarse salt on a napkin or in a saucer. Hold glass upside down, run a quartered lime around the rim, then lightly twirl it in the salt. Shake off excess so only a delicate crust of salt rims the glass. Or omit salt. Add tequila, fresh lime juice, and triple sec (or Cointreau) to a stainless steel shaker cup and fill 2/3 full of ice. Shake briefly until cup is frosty; strain into salt-rimmed cocktail glasses or pour over fresh ice. Dose yourself as you would a martini. Taste before serving because the acidity of limes varies greatly. Add more lime or sweeten with a splash of simple, diluted agave syrup, Cantina Classic syrups, or Sweet and Sour. Note: If you prefer a more potent margarita, use a 2:1:1 ratio.

[/symple_tab]

[symple_tab title=”Seasoned Salts“]

Master Recipe and Variations

from Viva Tequila! Cocktails, Cooking, and Other Agave Adventures | Serves 1

From this master recipe, you can make several versions of seasoned salts. Let it inspire your own creations. In small increments, add more sugar, citric acid, chiles, spices, and other ingredients to suit your own taste.

Ingredients

4 tablespoons kosher salt 1 1/2 teaspoons freshly grated lime zest 1 1/2 teaspoons freshly grated orange zest 1 tablespoon granulated or turbinado sugar 1/4 teaspoon citric acid Gently grind ingredients in a small bowl, using a bar muddler or mortar and pestle. The citrus zest will make the salt rather moist, so spread on a large plate to dry for several hours, stirring occasionally; add other flavorings. Store tightly sealed. Makes about 8 tablespoons.

[symple_divider style=”solid” margin_top=”20px” margin_bottom=”20px”]

Spicy Mexican Seasoned Salt with Chile and Lime

Add to 4 tablespoons master recipe: 1- 2 teaspoons sugar 1/4 teaspoon citric acid 1 teaspoon fine-quality paprika 1/4 teaspoon freshly ground chile de arbol, guajillo, or cayenne 1 1/2 teaspoons pure ground chile ancho

[symple_divider style=”solid” margin_top=”20px” margin_bottom=”20px”]

Hibiscus Flower and Orange Zest Salt

Add to 1 tablespoon master recipe: 1 teaspoon coarsely ground flor de jamaica (dried hibiscus flower) 1/4 teaspoon sugar 1/2 teaspoon orange zest 1/8 teaspoon citric acid

[/symple_tab]

[symple_tab title=”Simple Syrup“]

Simple Syrup

from Viva Tequila! Cocktails, Cooking, and Other Agave Adventures | Serves 1

Simple syrup (jarabe), an essential ingredient in any cantina, is a convenient remedy for sweetening mixed drinks. Unlike granulated sugar, simple syrup dissolves easily…and it’s simple to make. For a less sweet version, use a 1:1 or 1 1/2:1 ration of sugar and water.

Ingredients

2 cups granulated sugar 1 cup purified water In a heavy one-quart saucepan, bring sugar and water to a slow boil. Reduce heat and simmer, stirring gently for about 3 minutes, until sugar is dissolved. Remove from heat and cool. Pour into a clean glass bottle. Keep refrigerated for about a month. Makes approximately 2 cups.

[/symple_tab] [/symple_tabgroup]

Back to top [symple_divider style=”solid” margin_top=”20px” margin_bottom=”20px”]

Humanists & Scholars

For additional academic references, please see the following publications:

Tequila Reading List

|

|

|||||

| Viva Tequila: Cocktails, Cooking, and Other Agave Adventures | Tequila: A Natural and Cultural History | |||||

[symple_divider style=”solid” margin_top=”20px” margin_bottom=”20px”]

From ¡Tequila! A Natural and Cultural History:

“April, the cruelest month arrives. Its heat and dryness tans, burns, and blisters the skin of Mezcaleros. There is barely a cloud in the sky to buffer the field workers from the sun’s intensity. Their feet sink into the talc like soil broken open and baking. What soil the men don’t work by hand is churned and turned by tractors pulling plowshares, harrows and rakes.

If April’s winds prove unrelenting the precious soil is easily whipped up into dust devils that pelt the skin of anyone who remains unshielded from their assault in the field. Over time, the assailants’ faces become pocked and creased into deep furrows. Even when sombreros are worn to shelter them from the onslaught, their ever-reddening necks cannot escape the weather-beating. Whenever mescaleros pause in their labors during the heat of the dry season, they wipe away the salt stinging their eyes, and try to refocus. But as they reopen their eyes, they see that a heat mirage still wavers on the horizon and the ache in their hands still drones like a thousand cicadas at noon. There are some who suffer unmercifully from such solar exposure, breaking out with heat rashes so wretched that they cannot return in short order to the labor that wins them bread, wine, and soothing remedies.

When “hunger weather” rages down on tequila fields like this, the mescaleros can escape its rigors only by shifting their hours, arriving in the twilight before dawn. By six in the morning, all of them are fully embroiled in the tasks at hand. The work crews, called cuadrillas (squadrons), are expected to keep working right through the peak heat of the day. Nevertheless, by nine in the morning, one or two workings get restless and wander out of the fields to gather a few dry twigs for a cook fire.

They heat up a sheet metal Comal, place is over a meager bed of coals, and prepare a makeshift “brunch” at the field’s edge . There, the entire squadron comes together to eat, as well as to rest, and as they do so, they rekindle their debates from the day before. Their debates, of course, concert themselves, more often them not, with tequila, women, religion, or politics, or in some weird way, all of the above.

It is during such lollygagging that the bulk of extant folklore about traditional agave culture is transmitted, down to its finest details. It is done as the men are sitting amidst their tools and their dogs, hungrily waiting for the food to be warmed. The men have already emptied their plastic bags of the tacos and tortillas that they have brought from their homes; they have sautéed their chilies and beans, and once everything looks ready to eat, they hunker down to savor their meal. As the daily fare is consumed, a few of the men offer black-humored commentaries to the others, who have crowded beneath the little shade they can find. This shade, this refuge, this sanctuary of oral history often comes in the form of a partoa or parrot tree.

It is the definition of the dictionary…It is magnificent tree that forms a giant canopy, a mythical tree known elsewhere in Latin America as guanacastle and known by botanists as Enterolobium cyclocaprum. It is the only woody plant for miles in any direction that offers a modicum of shade. The parota is a patch of relief blues. During the months of April and May the dry pods of the parota are toasted over the coals along with the tacos and tamales, preparing their seeds for eating with salsa and salt.”

– Ana Valenzuala-Zapata

Back to top [symple_divider style=”solid” margin_top=”20px” margin_bottom=”20px”]

Music

Songs from The Tequila Chamber of Commerce

[symple_divider style=”solid” margin_top=”20px” margin_bottom=”20px”]

Extras

[symple_divider style=”solid” margin_top=”20px” margin_bottom=”20px”]

Types of Tequila

[symple_divider style=”solid” margin_top=”20px” margin_bottom=”20px”]

The Seven Steps of Making Tequila

Step 1: Harvesting

Tequila is a spirit made from the agave tequilana Weber, or blue agave plant. It can only be produced from agaves grown in five Mexican states: the entire state of Jalisco and designated areas in Guanajuato, Michoacán, Nayarit, and Tamaulipas. The agave plants take from eight to twelve years to mature. When ready, the jimador, or agave harvester, uses a machete, coa and other tools to remove the agave leaves. Only the heart, or “piña”, is used to make tequila. It takes approximately 15 pounds of piñas to produce one liter of tequila.

[metaslider id=2980]

Step 2: Cooking

[metaslider id=2985]

Step 3: Extraction

[metaslider id=2986]

Step 4: Fermentation

[metaslider id=2998]

Step 5: Distillation

[metaslider id=3002]

Step 6: Aging

[metaslider id=3007]

Step 7: Bottling

[metaslider id=3013]

[symple_divider style=”solid” margin_top=”20px” margin_bottom=”20px”]

Tequila in Popular Culture

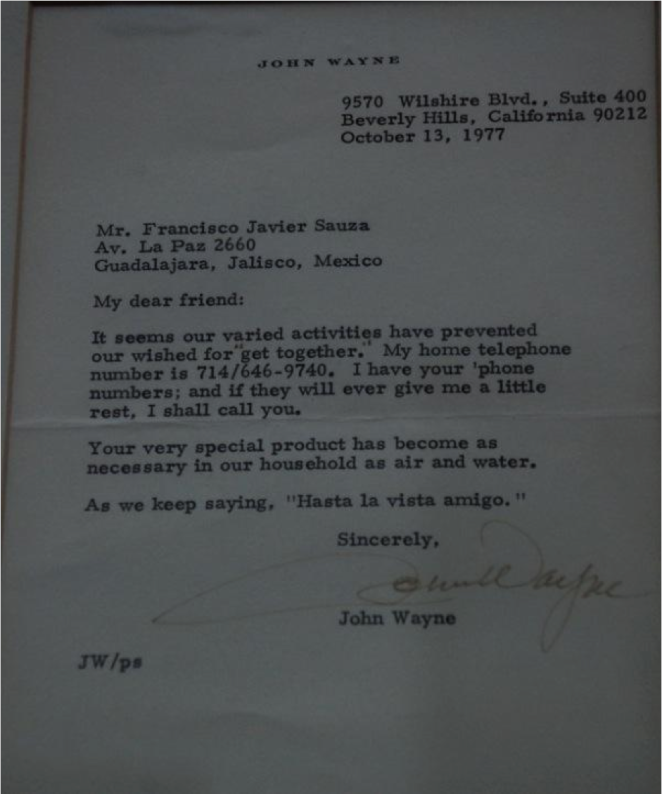

John Wayne’s Letter to Francisco Javier Sauza, 1977

Celebrities and Tequila

Back to top

[symple_divider style=”solid” margin_top=”20px” margin_bottom=”20px”]

Links

|

||||

| Tequila Interchange Project |